This week, we’re talking about Heathers, the 1989 black comedy film (not the 2010 off-broadway musical, although I could pontificate on that version for hours). Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Brooks,” you say, “I can’t help but notice that Heathers, the ’80s cult classic starring Winona Ryder and Christian Slater, is not a yearbook. What gives?” And yes, that’s true. You’re very observant and you get a gold star. But there is a through-line here, I promise.

On a recent rewatch, I was delighted to discover that Heathers employs ephemera in much of its storytelling. More than that, the film actively explores ephemera’s role in self-concept, identity performance, and posthumous character interpretation. With snark and satire, Heathers interrogates the iceberg theory our culture posits about adolescent identity: that teenagers are infinitely complex and sympathetic beings who contain far more substance than meets the eye.

A quick synopsis for the uninitiated (TW death, abusive relationship dynamics, suicide mention): Heathers is a dark comedy that satirizes the classic teen coming-of-age film. The protagonist, Veronica Sawyer, is a reluctant and morally conflicted member of The Heathers, the most powerful clique at Westerburg High School. She becomes romantically involved with new kid and “bad boy” Jason Dean (“JD”), who manipulates her into assisting him in the murder of three popular students — Heather Chandler, leader of The Heathers, and two douchey football stars. They avoid repercussions by staging each murder as a suicide, forging handwriting and planting murder weapons and other “evidence.” After seeing the superficial martyrdom and social carnage she’s helped to create, Veronica decides that enough is enough and… you’ll have to watch the movie to find out the rest. It’s available for free (with ads) on Tubi!

“Dear Diary…”

That’s Veronica’s first line in Heathers. The use of a diary as a framing device isn’t revolutionary, but Veronica’s diary has no bearing on the plot or the way the story unfolds; the object is only significant as an externalization of her inner world. Through it, we learn all of the ugly feelings she harbors for Heather Chandler and, later, JD.

Early on in the film, it’s revealed that Veronica can imitate anyone’s handwriting with ease, a skill that The Heathers often employ for a laugh at their peers’ expense — in one of the film’s first scenes, Veronica is pressured into writing a fake love letter from the quarterback to resident fat kid Martha “Dumptruck” Dunnstock. Her diary is her only safe haven, the only place her writing isn’t being manipulated by malicious forces. By covering its pages in her natural handwriting’s large, loopy letters, Veronica’s entries reflect the big, messy, authentic feelings she doesn’t want anyone to see.

As the film progresses, Veronica continues to entrust her diary with highly sensitive information, information that could expose her as an accessory to murder. Why? I believe the diary is more representational than literal. It works to communicate our protagonist’s honesty, moral character, and good intentions when juxtaposed with the other characters’ superficiality and opportunism. As we’ll see, this object is the only genuine reflection of a character’s inner world, the only physical document that doesn’t mischaracterize its (supposed) author.

“Oh, the humanity!”

When JD “accidentally” kills Heather Chandler, Veronica’s forgery skills come to the rescue. Still, her gift isn’t really hers to use and control: by creating a fake suicide note for Heather Chandler, her writing takes on a life of its own. She manufactures a false version of the Heather who terrorized the halls of Westerburg High — this Heather Chandler felt hurt and small and misunderstood. This Heather Chandler died “knowing no one knew the real me.”

The community digests Heather’s suicide note with ease, the cognitive dissonance between the Heather they knew and the sensitive and thoughtful soul reflected in the note easily explained away: she used cruelty as a defense mechanism and hid her “true self” from the judgemental eyes of her peers. This little piece of ephemera confirms what everyone always wanted to believe — that popular smoke-show Heather Chandler wasn’t ugly on the inside, that she was just as scared as everyone else, that she had problems, too.

There’s a short but significant scene featuring the yearbook club as they cope with the aftermath of the tragedy. (See? I brought it back around.) Editor-in-Chief Dennis sees Heather’s death as an opportunity to immortalize her as Westerburg’s patron saint… and sell more yearbooks.

Dennis asks Veronica if she has any access to anything else Heather created: “We were wondering if you had any poems... artwork that Heather did, that we can put in the Heather Chandler yearbook spread.” More than just another way to fill up the two-page spread, it seems like Dennis is searching for further physical evidence of the sensitive soul constructed by Heather’s suicide note, playing into the “tortured artist” stereotype.

The centrality of the note on the proposed spread is also significant: while it’s surrounded by photos of Heather as her peers actually remember her, the spread’s emphasis on her note shows that one piece of false ephemera is more meaningful to the students than their own memories. Overall, this short scene displays the yearbook’s role in manufacturing identities, showcasing how the format necessitates rosy, concise narratives when the reality is often messy and ugly.

It is also in this scene that Veronica learns that lewd rumors are being spread about her by star athletes Kurt and Ram. She and JD plan their revenge: shoot the boys with fake bullets and make it look like a gay lovers’ suicide pact. To really sell the narrative, they need more than a fake suicide note — JD acquires some “homosexual artifacts,” like mascara, a Joan Crawford postcard, and mineral water. (Happy Pride Month, I guess.)

Absurd cultural stereotypes coupled with a convincing suicide note forgery… the citizens of Sherwood, Ohio eat up this narrative, too. Kurt and Ram’s note weaponizes shame and stigma as the reasons for their secrecy and macho-man personas: The joy we shared in each other’s arms was greater than any touchdown, yet we were forced to live the lie of sexist, beer-guzzling, jock assholes.

By forging those notes, Veronica has rewritten three inner worlds, unwittingly martyring Westerburg’s biggest jerks. “Suicide gave Heather depth, Kurt a soul, Ram a brain…” she writes. “I don't know what it’s given me.”

“Eskimo”

So far, we’ve seen a community uncritically accept three manufactured identities as authentic. We’ve seen the way people trust objects to reveal the “true selves” of their owners, and how easily that trust can be manipulated.

All of this comes to a head when, in an elaborate dream sequence, JD kills Heather Duke, another member of the infamous clique. When Veronica refuses to forge another suicide note, JD is unbothered: “You don’t get it, do you? Society nods its head at any horror the ‘American Teenager’ can think to bring upon itself... Nobody’s gonna care about exact handwriting!” Armed with a knife, a half-assed suicide note, and Heather Duke’s underlined copy of Moby Dick, he disappears into his victim’s bedroom.

The proceeding funeral scene illustrates how, when presented with an object containing clues about someone’s “true self” (however threadbare), the citizens of Sherwood become willfully blind to anything else. (Literally — everyone in the chapel is wearing 3D glasses.) One word underlined in Heather Duke’s copy of Moby Dick, “Eskimo,” leads the priest to extrapolate on the state of her soul: it was “freezing with the knowledge of the way fellow teenagers can be cruel, the way that parents can be unresponsive […] the way that life can suck!”

We all make up stories about people based on their passive identity performance — the way they dress, the state of their living space, whether they dog-ear the pages of their books or use a bookmark. But when you’re holding something someone has marked up, like a letter or a diary or a yearbook or a paperback copy of Moby Dick, a physical and mental connection is constructed… there’s a sense that you really get them. Throughout Heathers, we learn how that connection can be twisted and warped, with “Eskimo” as the most potent (and absurd) example.

“Dear Diary, last entry”

In a clever and satisfying turn of events, Veronica finally uses her writing as a weapon against the person who deserves it the most: JD. Her final entry transforms her diary from a private safe haven to a piece of public documentation targeting him.

Dear Diary, last entry. No one can stop JD — not the F.B.I., the C.I.A. or the P.T.A. He once told me the extreme always makes an impression. Well, now it’s my turn. Let’s see how the son-of-a-bitch reacts to a suicide he didn’t perform himself!

In an act of self-defense, she fakes her own death, knowing that when JD finds her, he’ll fold just like the rest of them: duped by anything written with (alleged) sincerity in such a private receptacle. He had entered her room to kill her, armed with a .44 Magnum and a fake suicide note. Now, she’s taken back the narrative by beating him to the punch.

By unwittingly rehabilitating the character of popular kids from beyond the grave, Veronica has learned that the written word has an immeasurable amount of power. It can create and devastate relationships. It can construct false feelings, false identities, false realities. It can liberate, and, just as easily, destroy.

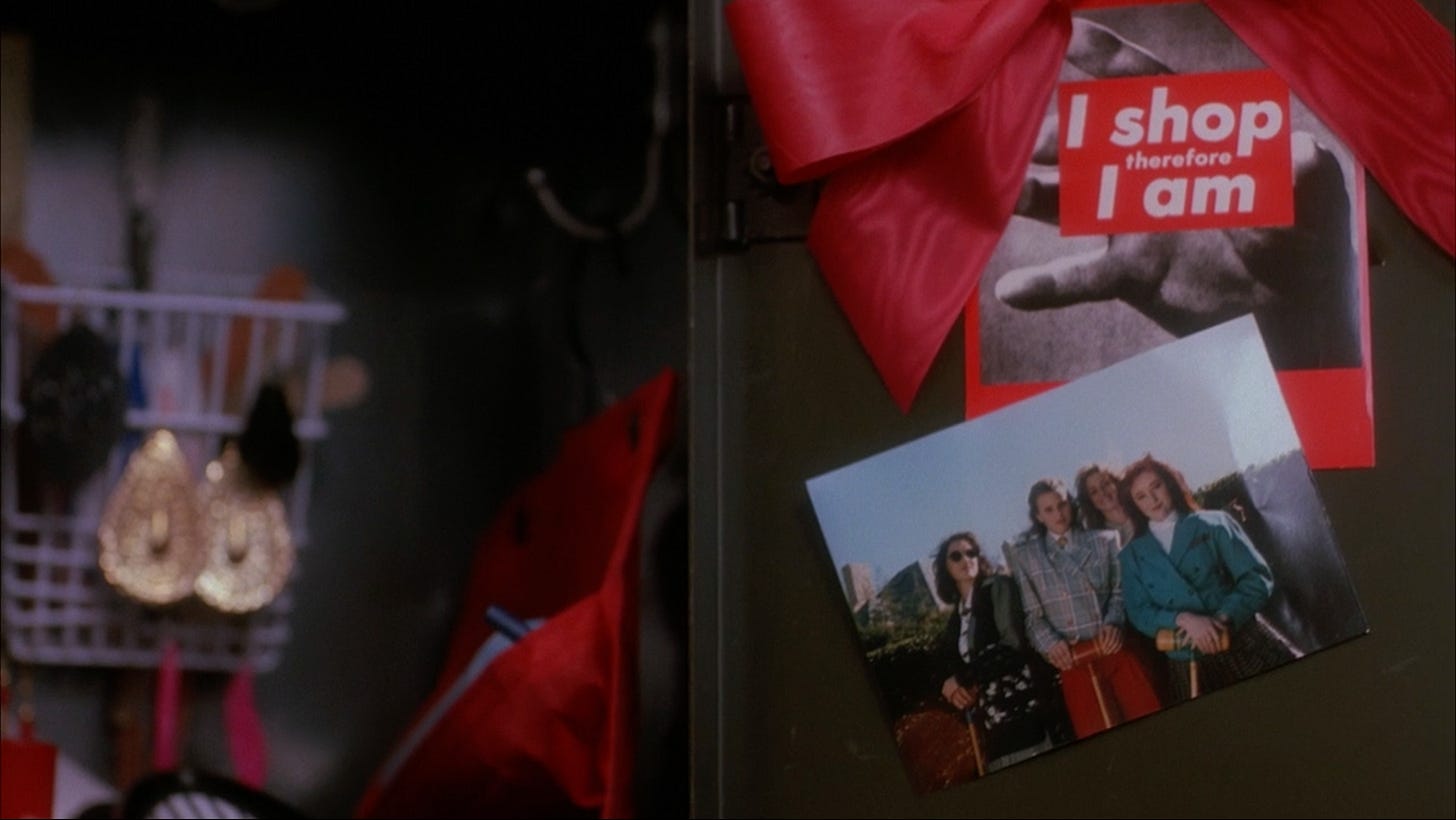

I’ll end by spotlighting one of my very favorite scenes from Heathers. It’s just 56 seconds long, but I consider it one of the most tender and genuine minutes of the whole film. In it, Veronica explores Heather Chandler’s old locker and is reminded of the very real, flawed, whole person she was.

These little items, these keychains and photos and earrings and bottles of nail polish, are the only pieces of Heather’s true identity left. It’s a private space Veronica isn’t supposed to be, and that’s where the truest version of Heather has been hiding all this time.

Tune back in next week for our regularly scheduled programming! I promise!