"I hope your future years will be full of excitement"

Navigating the gender binary in 1955, pt. II

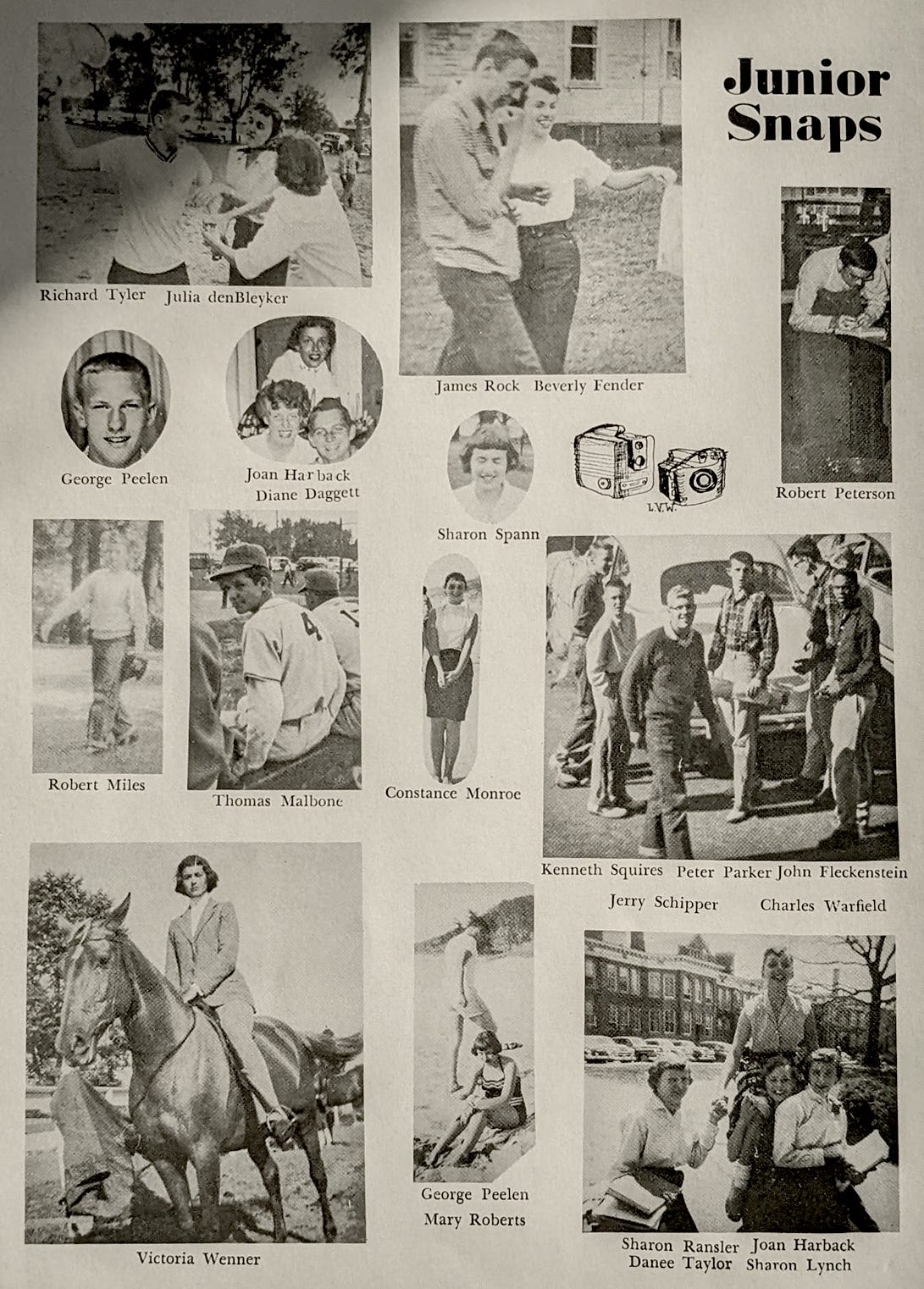

Last time, we met Connie Monroe, rising senior at State High School and a “real swell gal.” She’s got a lot going for her: with long curly black tresses, a seat on the prom decorating committee, and the know-how to write love letters to boys for her friends, it seems like she’s really doing this “womanhood” thing right.

But where do these gendered rules come from, and how did she learn to follow them so well? Was she born with it, or is it Maybelline? Luckily for our Connie, the instructions for fulfilling all of midcentury womanhood’s (often contradictory) expectations can be found in a plethora of instructional videos created by companies like Young America Films, Coronet Films, educational publishing giant McGraw-Hill. Here we can find the answers to all of our most pressing questions:

Is it okay to be popular? Yes, but only in moderation.

Am I allowed to talk about other people? Sure, if it doesn’t make you seem like a gossip.

How much affection should I tolerate from the boy I’m going steady with? Not too much.

How do I know if I’m really in love? Ask your mom — she’ll give you a checklist.

These films lampshade some real and pressing problems with the strict gender binary of the time — the delicate balance girls must strike between appearing sociable and demure, popular and mysterious, is treated as a simple and uniquely feminine expectation. This is often brushed aside as entirely unproblematic, “just the way things are”… and, we’re forced to assume, how they always have been. These narratives exist in a vacuum, including no past or future beyond the social norms of the day. In his short but fascinating exploration of Coronet Films, online commentator Big Joel observes that “There is no sense of history in these films.” Showcasing an exchange between the adolescent protagonist and her mother in How Do You Know It’s Love (1950), he wonders,

Is there any sense here that the 1950s middle-class understanding of courtship wasn’t always the way things were? Any sense that these parents lived through two World Wars and a Great Depression, all of which radically changed how they would have approached dating in their time?

The answer is an obvious and resounding “no”: as Big Joel points out, the adults in these movies “are only conduits by which we can learn how to function within the suburban middle-class societies of the 1950s” — the best, most modern, and most well-adjusted social framework in existence, according to Coronet Films.

This idealized, static depiction of “normalcy” is echoed throughout Connie’s copy of the Highlander, and nowhere more clearly than in its “Prophecy” for the Class of 1955. Reading this imagining of graduating seniors’ future lives feels less like looking into a crystal ball and more like looking through a window into the ’50s: no mention of flying cars or time travel, but plenty of midcentury gender stereotypes. (Okay fine, there is one mention of a 3-D television set.)

In this shining vision of the future, male graduates still get the big important jobs — Navy admirals, senators, Nobel Prize-winning chemists — with the gals tagging along as secretaries and assistants; dental hygiene assistant Karen Brower “might make for another good reason” to visit Phil Leach’s dentistry practice. Some career girls get to fulfill their own dreams, so long as the jobs are overtly feminine: interior decorators, stewardesses, fashion consultants, performers. (Ann Burgderfer single-handedly runs a school, but don’t get too excited — it’s a charm school.) Interestingly, “the local university” is presented as a haven of true gender equality, boasting both male and female professors from the State High class of 1955.

Is it possible that the young, wide-eyed, imaginative kids who edited this yearbook really thought that social norms wouldn’t — or couldn’t — change by the time they entered the workforce? Is Joan Newton satisfied being her classmate’s future assistant? Should Harriette Howe’s future be reduced to “nursing her man to the best of health”, or Connie Kuizenga’s to “psychoanalyzing men”? (Okay, maybe the answer to that last one is “yes” — who among us doesn’t enjoy psychoanalyzing men?)

It’s easy to Monday-morning-quarterback this kind of thing, to shake our heads and chuckle at the naïvete and narrowness of past generations’ future imaginings. But the authoritative tone that educational media adopted during this era could easily convince anyone of the “rightness,” the virtuous purpose of the midcentury status quo. Instructional films like the ones mentioned above present society as a machine in which every person is a cog with a set function to fulfill. Quoting Big Joel again,

The ideology of 1950s America […] wasn’t about autonomy or freedom; it was about efficiently and systems, about how to “act well” in a really restrictive culture, how to be a functioning piece in a giant machine.

It’s possible that for the students of State High, envisioning a successful, satisfying future meant envisioning where they fit into this system, not how they could forge their own unique paths.

It’s certainly easier to imagine the future when you have fewer options, especially as a recent high school graduate with your whole adult life ahead of you. I know that, though I entered “the real world” a while ago, I sometimes still crave order and rules and set benchmarks; I still wish there were some dude in a suit with a Transatlantic accent telling me what it means to succeed. Did Connie feel like she was succeeding in her role as Good Daughter, Good Classmate, Good Girl? Or did she crave something beyond the limitations of the yearbook prophecy and the instructions from the man on the screen?