"Flappers reigned supreme"

"When campus life was gay" and the role of nostalgia in collective identity

So here’s a fun fact about me you may not know: I had a pretty intense Roaring ‘20s phase in high school. You know how some teenagers have that one thing that takes over their whole life? Fall Out Boy or drama club or Doctor Who? Well I guess I was just built different. Forever the nostalgia junkie, and a frequent viewer of Chicago and The Great Gatsby, I dreamed of Charlestoning at speakeasies that served bathtub gin.

Don’t believe me? Here I am, in full flapper garb, on the day of my big AP US History presentation about the Jazz Age 👇

Luckily, I’m not alone in my obsession: the gals that created this Cedar Crest College yearbook also had Jazz Age fever. Upon first glance, you might mistake this 1953 edition of the Espejo for a ‘20s relic paying homage to the trends of the time. Alas, the yearbook is only ‘20s-themed.

But this prompts an interesting conversation about nostalgia’s role in the adolescent experience — why are these girls looking to the past, and what does their memory of the 1920s reveal about their lived experience in the early ‘50s? Espejo translates to mirror in English… what does this edition of the Espejo reflect about Cedar Crest College’s Class of 1953?

First, a bit of background: Cedar Crest College is a private liberal arts women’s college located in the Lehigh Valley. It’s tiny (currently enrolling 1,500 students, an assumed increase over the last century), and by the time the Class of 1953 graduated, it had been around for just over 50 years. Looking through the Espejo, you really get a sense of the intimate, tight-knit environment the institution cultivated: the students participated in song competitions, tugs-of-war, and a junior “prom.” In a way, it all feels very reminicent of high school.

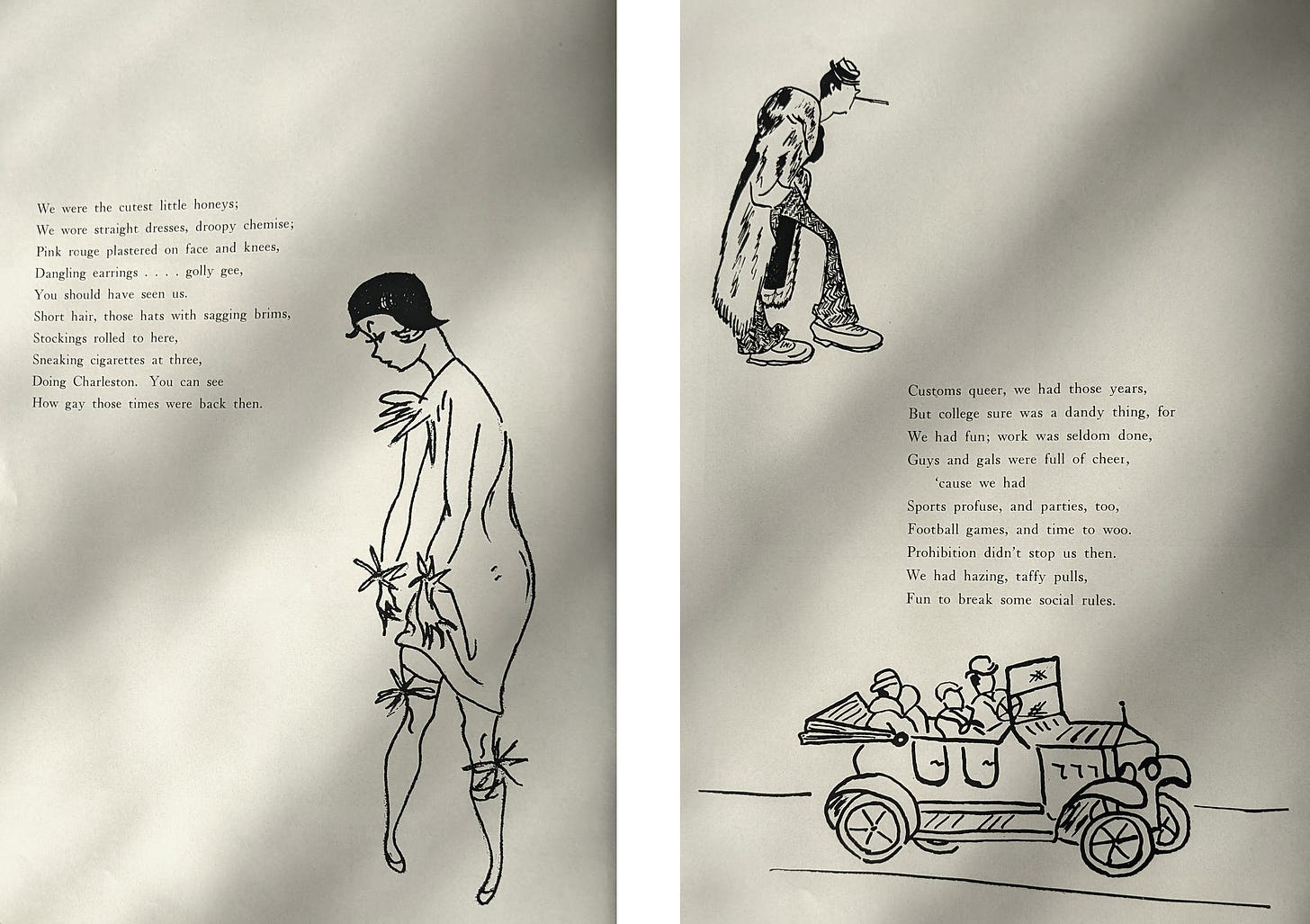

The yearbook itself takes the 1920s theme VERY seriously — underclassmen are gay blades and seniors are flappers, while faculty members are those dreaded prohibitionists. Each section starts with a silly illustration of dancing dandies and flappers, accompanied by a little poem reminiscing about those “gay old days.”

All this begs the question… why the 1920s? Why are these young women so enamored with a period characterized by youth and debauchery and excess? Maybe it’s not personal; maybe it’s just what everybody was into in 1953. There’s a theory that cultural trends run on a 30-year cycle, that “a critical mass of people who were consumers of culture when they were young […] become the creators of culture in their adulthood.” Maybe these adults, nostalgic for their youth (which just so happened to take place in the 1920s), were pumping out a rosy, romanticized version of the 1920s and the gals in the yearbook club were just piggybacking off of the trend.

But I’m not satisfied with that explanation; I want to dive deeper (surprise surprise). The 30-year trend often leads similarities between the past and present to be emphasized, so maybe the girls of Cedar Crest College saw themselves reflected in the experiences of their predecessors. After all, the ‘20s and ‘50s were both post-war periods of relative economic security, and both were times in which “youth culture” in America was becoming more visible, insistent, and rebellious. Maybe the Class of 1953 looked back at the Class of 1923, with their dancing and drinking and (gasp!) ankle-flaunting, and thought, “I know how they feel.”

Still, the reason behind their fascination could just as easily lie in the perceived differences between the “Roaring ‘20s” and ‘50s, America’s more stable “Golden Age.” It seemed like, in the wake of the first World War, the world was opening up for women: they had just won the right to vote, and the brazenly boyish Flapper was quickly replacing the waifish feminine ideal of the Gibson Girl.

Contrast that world with the one these Cedar Crest soon-to-be grads were living in: options for women, even well-educated ones like them, were becoming more and more constricted, a big “PSYCH!” pulled on those who joined the workforce during World War II and were subsequently pushed back into the home afterward. Even in the oasis of academia, there was an overt acknowledgment that many Cedar Crest girls would become homemakers; the school’s home economics club, which only extended membership to Home Ec majors, had far more members than organizations like the Gavel Society, a debate and speaking club open to anyone.

It’s clear that the Cedar Crest girls latched onto the youthful mischievousness of the 1920s, creating a nostalgic caricature that they could relate to. There’s a sort of jovial rebelliousness woven throughout the Espejo — nights of illegal drinking and late-night galavanting are celebrated, and evading the wrath of the “prohibitionists” (the faculty) is seen as nothing more than a fun game. These bright and vivacious young women wanted to rebel in the few ways they could before entering an adulthood filled with filing and shorthand or diaper-changing. The result? Romanticizing the 1920s as a vehicle of that wish-fulfillment, thinly veiled as simple nostalgia.

If there’s one thing I understand, it’s the joys of waxing nostalgic on a time I’ve never experienced — that’s what this newsletter is all about! The Cedar Crest girls imagined the thrill of Charlestoning and drinking the night away, divorced from any real-life struggles or consequences bootleggers and gender-non-conforming folks faced. And here I am, superimposing my feelings from adolescence onto those same Cedar Crest students: I became obsessed with the 1920s as a way of escaping my mundane modern life, celebrating my awkward boyishness, and imagining a world in which I feel rebellious and free, rather than stifled and terrified.

Who knows — maybe the Cedar Crest College Class of 1953 (much like Barry B. Benson) just really liked jazz. But our shared love of the Jazz Age connects us across states and centuries, a truly remarkable feat. Like the letter above, in which the yearbook’s editor affectionately addresses inhabitants of a past era, this exploration of the 1953 Espejo is my attempt to say:

Things may have changed

But we’re just the same as you were then.

This is very cool. I think of the 20s revival in fashion being more of a 60s thing, it's odd to see it in 1953. I wonder whether a coed school would have featured it, or if the ethos appeals more to women?